From record-breaking stays in space to a "knife-wielding orca," it has been a busy week in the world of science news. But the story that has most captured our imagination is that of what Earth could look like 8 billion years into the future. The exoplanet KMT-2020-BLG-0414, located 4,000 light-years from ours, is a rocky world that orbits a white dwarf — a hot Earth-size core from a sun that has exhausted all its nuclear fuel, just as Earth's sun will in billions of years.

However, before the sun shrinks to this diminutive size, it will expand into a red giant, which threatens to swallow Earth alongside Mercury and Venus. If our planet survives, then we may well resemble KMT-2020-BLG-0414. Whether humanity will be there to see it …

Lost Biblical tree resurrected from mystery seed

For 14 years, researchers have been growing a tree from an ancient seed that archaeologists excavated from a Judean Desert cave in the late 1980s. Now that the specimen stands at around 10 feet (3 meters) tall, the scientists believe that the tree grown from this 1,000 year old seed could belong to a long-lost lineage mentioned in the Bible.

The seed of the tree, dubbed "Sheba," dates back to somewhere between A.D. 993 and 1202, and the researchers believe that the fully-grown specimen could be the source of Biblical "tsori" — a resinous extract associated with healing in Genesis, Jeremiah and Ezekiel.

"The identity of Biblical 'tsori' (translated in English as 'balm') has long been open to debate," the researchers wrote in the study. Now, having revived Sheba, the team thinks it has finally unraveled its mystery of this ancient plant.

Discover more archaeology news

—2,700-year-old shields and helmet from ancient kingdom unearthed at castle in Turkey

—Mysterious 'horseman' from lead coffin unearthed in Notre Dame Cathedral finally identified

When was steel invented?

Steel is the backbone of the modern world and used in houses, skyscrapers, automobiles and more. But steel isn't found in nature, so when did humans invent steel?

Near-indestructible '5D memory crystal' could survive to the end of the universe

Scientists have developed a new data storage format that, under the right conditions, could survive well beyond the destruction of Earth as it gets consumed by the sun, and possibly until the very end of the known universe. Most data storage systems degrade over time, but researchers at the University of Southampton in the U.K. made a synthetic "5D memory crystal" that mimics the properties of fused quartz, one of the most chemically and thermally stable materials there is.

And what have they done with this incredible new material? They etched a copy of the entire human genome on it, in the hope that our species could be revived long after our extinction — however unlikely that may be.

Discover more technology stories

—What is artificial general intelligence (AGI)?

Also in science news this week

- Nuking an asteroid could save Earth from destruction, researchers show in 1st-of-its-kind X-ray experiment

- 1st-ever observation of 'spooky action' between quarks is highest-energy quantum entanglement ever detected

- Pollen allergies drove woolly mammoths to extinction, study claims

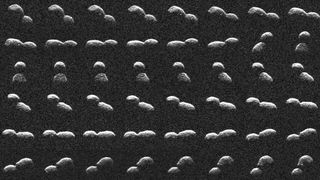

NASA reveals images of enormous, snowman-shaped asteroid

We're no strangers to "potentially hazardous" asteroids, given that as of September 2024, NASA has identified more than 2,400 known asteroids that will pass within 4.65 million miles (7.5 million kilometers) of our planet. While "potentially hazardous" sounds alarming, that's roughly 20 times the average distance between Earth and the moon, and astronomers do not believe any of them threaten our home for at least the next 100 years.

However, when they do pass, it gives us an opportunity to study asteroids in greater detail than when they are farther away from us. One such asteroid flew safely past Earth at a distance of 620,000 miles (1 million km) earlier this month, and new images captured by the Goldstone Solar System Radar near Barstow, California, reveal the "snowman" shaped rock is actually two asteroids locked together by their own gravity — known as a contact binary.

Something for the weekend

If you're looking for something a little longer to read over the weekend, here are some of the best long reads, book excerpts and interviews published this week.

- Our pick of the best science books for kids and young adults [Reading list]

- Will language face a dystopian future? How 'Future of Language' author Philip Seargeant thinks AI will shape our communication [Interview]

- 32 of the world's smartest animals [Countdown]

Science in pictures: 'Scuba-diving' lizards

When danger lurks for certain semi aquatic lizards, there is one place they can hide — underwater. But how can they stay there long enough to avoid predation? A clever trick, whereby they create an air bubble on their forehead to store oxygen, allowing them to breathe underwater like a scuba diver.

This behavior was first discovered in 2018, but a recent study found that the bubble allowed them to stay underwater 32% longer than without it. "We know that they can stay underwater at least about 20 minutes, but probably longer," study author Lindsey Swierk, assistant research professor in biological sciences at Binghamton University in New York, told Live Science in an email.

Follow Live Science on social media

Want more science news? Follow our Live Science WhatsApp Channel for the latest discoveries as they happen. It's the best way to get our expert reporting on the go, but if you don't use WhatsApp we're also on Facebook, X (formerly Twitter), Flipboard, Instagram, TikTok and LinkedIn.

评论(0)