Astronomers have discovered a pair of young stars near the supermassive black hole at the heart of our galaxy. And despite living so close to the cosmic behemoth, they are likely to remain intact for a million years.

While our pocket of the universe is home to a solitary sun, that's not the norm. More than half of all stars in the sky have one or more companions, yet until now, none have been found near a supermassive black hole. Astronomers attribute this absence to the extreme gravity black holes, which tug unevenly on nearby stars, making such multiple-star systems unstable and potentially kicking one of them out on lonely, high-speed journeys through the Milky Way.

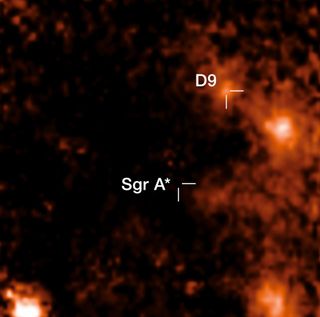

But the newfound duo, dubbed D9, suggests that some stellar pairs can, in fact, hang on near a black hole, if only for a short while. Astronomers estimate the stars are about 2.7 million years old, with one weighing roughly 2.8 times the mass of the sun while its companion may be just t 0.7 solar masses. Locked in a gravitational dance, they skirt Sagittarius A* (Sgr A*), the supermassive black hole lurking at our galaxy's center, as close as 0.095 light-years. Yet the fact that the two stars have not been torn apart and shredded suggests "black holes are not as destructive as we thought," Florian Peißker, an astronomer at the University of Cologne, said in a statement.

He and his colleagues describe the D9 stars in a paper published Tuesday (Dec. 17) in the journal Nature Communications.

In the nick of time

Peißker was using the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope (VLT) in Chile, to study mysterious G objects near our galaxy's center — apparent clumps of gas and dust that exhibit star-like behavior, whose true nature has eluded astronomers — when he noticed the orbit of one object wobbling strangely.

So, every night for 15 years, he used VLT to monitor changes to the wobbling object's wavelengths of light, which revealed how much ionized hydrogen the object emitted — in turn revealing a regular 372-day pattern. This periodic fluctuation was caused by the "Doppler Effect," in which wavelengths of light are stretched or smooshed as an object passes by them. This 372-day pattern was evidence that the "object" is actually two stars caught in a gravitational dance around our galaxy's center, the researchers said.

The researchers estimate the newfound stars ignited just 2.7 million years ago and will eventually succumb to the black hole's gravity, merging into a single star within a million years.

"This provides only a brief window on cosmic timescales to observe such a binary system — and we succeeded!" study co-author Emma Bordier of the University of Cologne said in the statement.

A sneak peek of hidden stars and planets

Beyond being a technological feat, this discovery could help explain why similar binary pairs haven't been detected near our galaxy's center. There, the mysterious G objects that appear to be clouds of gas and dust may instead be binary stars about to merge, like the D9 pair, or remnant material from past mergers, researchers say.

As the clouds of dust and gas around these binary stars dissipate, the stellar duos would be reborn as single, youthful stars that have been observed zipping around the Milky Way's center at hypervelocities, the new study suggests.

Moreover, because young stars are often accompanied by planets, this discovery also raises the possibility of finding orbiting worlds near black holes, Peißker said in the statement.

"It seems plausible that the detection of planets in the galactic center is just a matter of time."

评论(0)