A male humpback whale crossed at least three oceans in search of sex, a new study shows.

The whale's journey is the longest great-circle distance between two sightings ever recorded for the species (Megaptera novaeangliae), scientists said. Great-circle distance refers to the shortest distance between two points on Earth as measured on the planet's spherical surface.

Beginning off the coast of Colombia in the eastern Pacific Ocean and ending off the coast of Zanzibar in the southwest Indian Ocean, the whale's odyssey took it 8,106 miles (13,046 kilometers) across the globe, the researchers said.

The whale likely swam eastward from Colombia, riding on prevailing currents in the Southern Ocean and potentially visiting humpback whale populations in the Atlantic Ocean, said study co-author Ted Cheeseman, a doctoral student at Southern Cross University in Australia and director of Happywhale, an image database where the researchers collected evidence for the study.

"This was a very exciting find, the kind of discovery where our first response was that there must be some error," Cheeseman told Live Science in an email. Together with the astounding mileage, one of the most important findings from the study was that the whale dropped in on several humpback whale populations along the way, exploring farther afield than any other humpback whale known to science, Cheeseman said.

Related: Watch heartbreaking footage of humpback whale with missing tail in Washington state

Humpback whales usually follow very consistent migration patterns, moving between feeding grounds in cold waters near the poles and breeding areas closer to the tropics. The whales are known to swim more than 5,000 miles (8,000 km) in the north-south direction every year, but they don't tend to travel far in the east-west direction and generally don't mix with other populations.

The cross-ocean journey observed in the new study shows that humpback whale migrations are more flexible than researchers previously thought. While scientists have occasionally recorded similar migrations before — such as the case of a female humpback whale that swam 6,100 miles (9,800 km) from Brazil to Madagascar between 1999 and 2001 — the male in the new study has set a new distance record while traveling from one breeding area to another.

"We've been able to document novel behavior which provides important insight into [humpback whales'] ecology," study lead author Ekaterina Kalashnikova, a biologist working with the Tanzania Cetaceans Program and the Barazuto Center for Scientific Studies in Mozambique, told Live Science in an email.

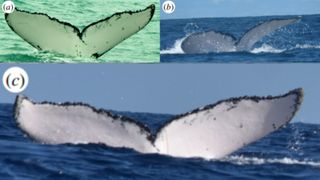

The discovery is based on photographs the researchers took between 2013 and 2022, and which they subsequently posted on Happywhale. The pictures showed the same sexually mature male in two locations off Colombia, and then five years later in the Zanzibar Channel, each time in the company of a competitive group — a group of whales in which a female is closely guarded by a male "principal escort" and other males compete for access to her, Kalashnikova said.

The motivation for the journey was probably sex, with the male in question increasing his chances of reproducing by mingling with members of another breeding population. Other reasons for the whale's unusual adventure could be to do with environmental shifts that impact the distribution of food; climate change; and humpback whale population growth, which boosts competition between males during the feeding and breeding seasons, according to the study.

The research was published Tuesday (Dec. 10) in the journal Royal Society Open Science.

评论(0)