Napping after overfeeding on food is a dilemma many of us will be fortunate to face on Christmas Day. New research has shown that, billions of years ago, some early black holes also had to nap after overindulging.

Using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST), astronomers spotted a dormant supermassive black hole that existed just 800 million years after the Big Bang. This cosmic monster passed out after a particularly large meal of galactic gas and dust.

The black hole is extraordinary for its monstrous size. With a mass around 400 million times that of the sun, it is the most massive black hole seen by the JWST in the early universe. The discovery, published Dec. 18 in the journal Nature, further complicates the mystery of how supermassive black holes got so massive so quickly in the early universe.

The mass of this supermassive black hole also stands out because when these cosmic titans are usually found in the local (and recent) universe, they possess around 0.1% of their host galaxy mass. This supermassive black hole has a mass that is equivalent to around 40% of its host galaxy's mass.

Scientists would expect such a gigantic black hole to be voraciously feeding and thus growing. Yet this black hole is gobbling up gas at a very slow rate, around a hundredth of the maximum possible accretion limit for a black hole this size.

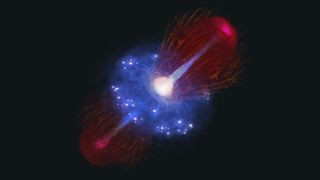

Because black holes have outer boundaries called "event horizons" that trap light (and everything else that passes them), if they aren't greedily feeding and lighting up that matter, they tend to be invisible.

When they are surrounded by matter in a flattened cloud called an accretion disk that gradually feeds them, the gravitational influence of supermassive black holes causes immense friction, which causes this cosmic larder to glow. This emission allows us to detect supermassive black holes.

This dormant supermassive black hole was different, however. That's because its tremendous mass granted it a huge gravitational influence that made it visible.

“Even though this black hole is dormant, its enormous size made it possible for us to detect," team leader Ignas Juodžbalis from Cambridge’s Kavli Institute for Cosmology said in a statement. "Its dormant state allowed us to learn about the mass of the host galaxy as well.

"The early universe managed to produce some absolute monsters, even in relatively tiny galaxies."

Why are early monster black holes such a big problem?

Since the JWST began making observations of the cosmos in 2022, the powerful instrument has discovered supermassive black holes at earlier stages of the universe.

Supermassive black holes are cosmic titans with masses equivalent to millions or even billions of suns. Unlike stellar mass black holes, which form when massive stars collapse, supermassive black holes are thought to grow via a chain of mergers of subsequently more massive black holes and from a steady diet of gas and dust from their host galaxies.

This process is thought to take over one billion years to create a supermassive black hole with a mass even at the lower scale of these monstrous masses. That means spotting a supermassive black hole in the recent history of our 13.8 billion-year-old cosmos isn't problematic.

However, the JWST finding these cosmic titans when the universe was younger than one billion years old, sometimes as early as 600 million years after the Big Bang, is problematic. The tremendous size of this early black hole and the fact it isn't even growing rapidly by feeding makes this problem even more confusing.

"It's possible that black holes are 'born big,' which could explain why the JWST spotted huge black holes in the early universe," team member and Kavli researcher Roberto Maiolino said. "But another possibility is they go through periods of hyperactivity, followed by long periods of dormancy."

Black holes push it past the limit to overfeed

Maiolino and colleagues revisited the problem of supermassive black holes in the early universe by running simulations of their growth mechanisms. The team found that the most likely explanation was that black holes could briefly exceed the limit placed on accretion.

This feeding cap is known as the "Eddington limit." It suggests that any ravenously accreting celestial body will reach the point at which the radiation its feeding pumps out will push away material, cutting off its food supply.

This team thinks early black holes could experience spates of overfeeding or "super-Eddington accretion." During these periods, greedy black holes would grow at hyper-accelerated rates. This would last for between 5 and 10 million years, after which the black hole would "nap" for 100 million years.

"It sounds counterintuitive to explain a dormant black hole with periods of hyperactivity, but these short bursts allow it to grow quickly while spending most of its time napping," Maiolino said.

The dormancy period of these black holes lasts 10 to 20 times longer than the phase of super-Eddington accretion, which means astronomers are more likely to catch these cosmic titans during their nap time than at dinner.

The discovery of this titanic napping black hole is a breakthrough for this theory.

This monsterous early black hole may just be the tip of the iceberg, with the team suspecting that the early universe could be replete with these sleeping giants. Unfortunately, the dormant nature of these monsters will make them difficult for astronomers to discover.

"It’s likely that the vast majority of black holes out there are in this dormant state – I’m surprised we found this one, but I’m excited to think that there are so many more we could find," Maiolino concluded.

Originally posted on Space.com.

评论(0)